1965

Out in Jersey’s bitter cold, the moon full, the trees rustled. Mama and I spent half the night shivering, huddled together on a bus bench—my head on her lap.

“M-Mama,” my teeth chattered. “I’m cold.”

“I am, too. Now, stay still.”

“But I’m hungry.”

“I know, Mary. Close your eyes. That bum. Where is he?”

We would have frozen if a kind woman hadn’t invited us up to her place to sleep on her sofa overnight.

Whenever Mama cornered Jimmy in a bar, drinking his pay away, after bickering over dinero, she’d remain with him. If I happened to be around, they sent me away, or Mama left me at home by myself. It saddened me how she preferred being with him rather than with me. Often, they’d stagger home and pass out in a stupor. Only then did the arguments cease and the fights end.

More often than not, I’d gone to bed with the sound of my stomach rumbling. Mama and Jimmy routinely barged in from a night of carousing.

“Mama, I’m hungry,” I mumbled, rubbing the sleep from my eyes.

“Why are you awake?”

“Can you fix me something to eat?”

“Oh, for goodness’ sake. It’s late.” She turned on the hotplate to fry a hot dog. A few minutes later, she’d have one for me rolled inside a slice of bread. “Here. Sit up.”

“Fix me one, too,” Jimmy demanded.

“Hold your horses,” Mama snapped.

As soon as I finished, I lay back down, my eyelids heavy. Eventually, the bright lights in the room faded. My parents’ fussing drifted away as sleep overtook me, but not before I heard familiar sounds. A can is popping open. Cursing. A slap. Sobs.

Unsure as to why, one evening Jimmy overturned the bed that Mama and I slept in. We tumbled onto the hard floor. As Mama struggled to rise, Jimmy pulled her by the arm and shoved her into a windowpane. Jimmy became aware of my presence, and after he flipped the bed upright, he ordered me back into it. I faced the wall, sniffling until I fell asleep.

The next morning, I awoke to the sight of a blood-spattered Mama hobbling on crutches. I ran to help her.

“Mama, what happened?”

“It’s nothing, Mary. Stop crying! I tripped, that’s all.”

I couldn’t help but wonder, Why did she think I didn’t know anything?

I knew some things. I hid loose change and planned to save enough money to take care of Mama one day. In my childish mind, I knew that one day we were going to live in a big house, have plenty to eat, and Mama wouldn’t ever have to worry again.

That afternoon, I heard cursing and knew it wasn’t good. A rattling sound echoed around the wall, as if something were whirling in a container. Then, to see Jimmy shaking my pink, plastic kitty bank upside down in mid-air, my pennies, dimes, and nickels clattering onto the floor, made me feel weak and sick inside.

I followed the coins that rolled under a chair and dove for them. I looked up, my eyes darting between Mama and Jimmy, hoping she’d do something. Mama called him a “jackass,” but that didn’t stop him. He couldn’t care less that I knelt there sobbing. He expressed zero shame as he scooped the scattered change into his pocket. My coins.

Later, Mama told me that Jimmy was just thirsty and to stop sniffling. “He’ll return the money soon enough,” she said. I knew that wasn’t true.

On my knees, I gathered up the broken pieces of my kitty bank. With no more tears left, I seethed, thinking, maybe Mama can take care of herself. And maybe I’ll never talk to her again. Or to Jimmy. And maybe I’ll run away . . . to my real daddy.

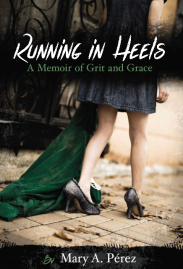

(Excerpt from Running in Heels – a continuation of Part I)

© M.A. Perez 2014, All Rights Reserved